Sonata for Unaccompanied Achilles

One of my earlier pieces of writing, approx. March 2013. It was a lot of fun writing this, even if now I’d be more careful with the technical words used. Runner-up in the Dame Ivy Compton-Burnett Prize for Creative Writing (Pembroke College, Cambridge).

One evening in the home, a blackout drives the patients into a state of panic, sending the orderlies running after them. Achilles is in his room, remarkably calm. Just before the power cut, he had been gazing through his window at the stars over this warm, dusty corner of Italy, or Greece, or wherever he is, listening to one of Bach’s sonatas for unaccompanied violin. It’s a favourite of his, because it seems as though there ought to be some accompaniment to this lone voice that Bach left to be filled in by the listener’s imagination. Perhaps he never intended accompaniment, Achilles thought, since the piece works just fine on its own, or maybe the accompaniment is hidden within the piece. But that was just speculation. In the silence, Achilles notes that the room is as black with his eyes open or closed. After feeling his way to the telephone, like every other night of his stay here, he calls his friend whom he met in a previous home before he was transferred here.

Achilles: Ciao my friend!

Achilles: I missed you too! It had been a while since our last conversation. When was that?

Achilles: So it was! You have been busy since then, haven’t you? I hear you have abandoned composing music for neuroscience, of all things?

Achilles: It all sounds fascinating! Say, I have been stuck on a question recently that might have its answer in your field of research; perhaps you can help me? I have contemplated it for months, and humankind has wrestled with it for millennia.

Achilles: No, no, I doubt it will take us very long, especially with someone as wise as you answering. It is the question of Consciousness; why do we experience anything? Why are we not just a mere unconscious sack of interacting molecules and cells? I just don’t get it! Moreover, I am quite stumped as to what field is best placed to answer it; do you think it is a physical question or neurological?

Achilles: You seem sure. But, so far, only in quantum physics has a conscious observer had any role to play in apparently ‘objective’ experiments, like the famous Double Slit experiment, where an observer changes the behaviour of electrons passing through a double slit. It’s the only place in science where a ‘philosophical zombie’ cannot be replaced by a conscious observer! Neuroscience can explain behaviour to us, but so far, explains nothing as to how pain fibres feel painful when active, or why we experience the redness of red. It seems that neuroscience cannot answer this problem, David Chalmers’ ‘Hard Problem of Consciousness’.

Achilles: Ah but such an exotic explanation might be necessary, since all normal modes of inquiry have failed entirely. Perhaps it involves some sort of self-reference, granting the brain awareness of its own processes. Then we would be aware of our thoughts as we think them!

Achilles: Philosophical zombies, yes you are right, could still have a brain that is responsive to its own internal workings. We’re back to square one. I think we may have to wait until some philosophical paradigm shift in how to address it before anyone can really understand it. Perhaps we should cut our losses and discuss something else.

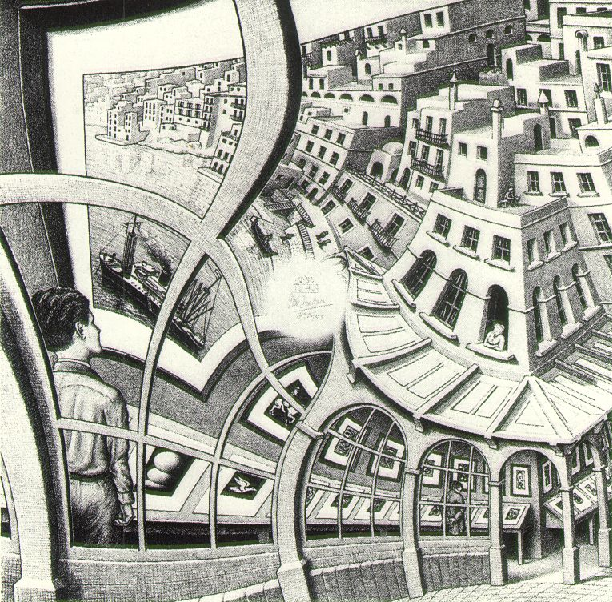

Achilles: Actually, as it happens, I did have something in mind! As you know, I am a keen studier of art, especially of M.C. Escher. Are you familiar with his work, ‘Print Gallery’?

Achilles: Literally in front of you? Excellent! I’m sorry to hear you find it too perplexing. With some study, I believe you will come to appreciate it. You will see that it depicts a man in a print gallery, who is looking at a print of a seaside town, perhaps Maltese, to guess from the architecture, and the town contains a print gallery in which stands a man looking at a print of a town containing a print gallery in which…. You get the idea. Do you see the blank space in the centre of this spiral where Escher signed it?

Achilles: I beg you to bear with me! It really is a true wonder when you look deeper. You were right, that point is the point around which the piece changes back into itself! Without this point, the work would have been impossible. Escher could have made that blank space as small as could be printed, but it can’t be non-existent! In the true Gödelian sense, the drawing has to be incomplete, because it is self-referential. And Escher knew it. And he forces another, more personal paradox upon us, since we too are looking at a print in which someone is looking at a print, in which there is someone looking at a print… He makes us think, for a second, that our universe is like the drawing. But I digress. I wanted to ask you, do you think it would be possible that a conversation (a dialogue, say) could have a similar point?

Achilles: Precisely! Now you’ve got it! A singularity!

Achilles: Yes, I have got it! Yes, a singularity! Personally, I see no reason why a dialogue couldn’t have such a point, a point around which things reflect to answer itself, yet continue to flow as the same entity. It would be like a one-dimensional version of ‘Print Gallery’, in that it answers itself, reflecting around a singularity! Yes, I do imagine that such a self-answering conversation is possible.

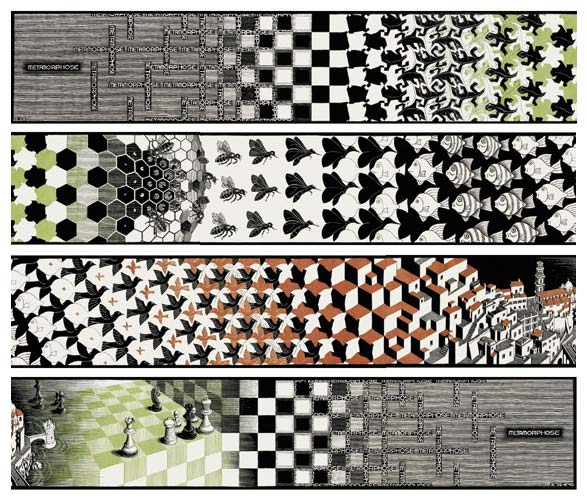

Achilles: I see. That point in the work might also be considered analogous to the ‘Metamorphosis’ segment of Escher’s Metamorphosis II (which I prefer for its simplicity) because its end answers its beginning while centring around that point… That is rather an intriguing feature. What more have you to say on it? It strains my mind to look at it. Wouldn’t you rather discuss another of his works?

Achilles: Oh yes I know that one. Strangely, I have a copy in front of me as we speak! I do find it a bit too perplexing for my taste, however.

Achilles: My my… Agreed, we will drop it for now; it is all very confusing for my scrambled brain. How about discussing my latest research? Or did you have something else in mind? My research concerns schizophrenia, particularly a hard problem involving auditory hallucinations. I am not so much concerned with what they are (anyway, I wouldn’t recognise one if one screamed in my ear), but I’m more interested in how they are caused. Such incomplete, scrambled minds are blindingly tricky nuts to crack. If you had any insight into it, maybe we could discuss that if you want?

Achilles: Excellent suggestion! Though I wonder if philosophical zombies might again shed any light on such speculations… But ah! I think the hard question still remains. Although it was a useful suggestion.

Achilles: … perhaps you have a point. But I am still doubtful about resorting to as exotic an explanation as that. In any case, it would certainly be a paradigm-shifting discovery! Our brief discussion has sparked my interest; maybe your suggestion would be an interesting line to take in my research…

Achilles: You mean to say that the answer might not belong to my field!? It must be neurological, isn’t it obvious? It simply can’t be anything else. Just wait until we neuroscientists figure it out.

Achilles: You always have been full of questions, my friend. I will certainly try! Being a scientist, I feel obliged to ponder at least briefly on any inquiry. But perhaps such a grand question had better be left for an occasion when we have more time?

Achilles: I know. It has been a refreshing experience. I do love probing the nature of the Universe and of ourselves. Although I’ll never say no to a good chat about art from time to time!

Achilles: Ah, it must have been during our stint playing characters in the book ‘Gödel, Escher, Bach’. Things were different then… Anyway, it had been much too long.

Achilles: Ciao, dear friend. I missed you.